Stateless widgets

There are cases where you’ll create widgets that don’t need to manage any form of internal state, this is where you’ll want to make use of the StatelessWidget. This widget doesn’t require any mutable state and will be used at times where other than the data that is initially passed into the object.

For example, we can look at several widgets that we know of which are stateless widgets:

All three of these widgets here are just a few of the stateless widgets from the flutter widget catalog. But what exactly makes these stateless? To begin with, it really helps to dive into the source of these widgets (I won’t do this in this post but you can view the source for the Text widget here). If we open up the source for say, the Text widget, we’ll notice that there is no state of the widget which can be changed. The Text widget is instantiated using a constructor and then these properties are used to build the widget to be displayed on the screen — the parent widget is essentially in control of managing the state which is presented by this widget.

So in the case of the Text widget — this is passed properties such as text, alignment, direction etc by it’s parent which it will then use as its configuration. The same applies to the other stateless widgets that I briefly mentioned.

But what if we’re creating our own widgets, when should we used a stateless widget? To think of a few examples:

- You may create a custom ProgressBar widget that just uses the properties which it is instantiated with to display progress to the user. This wouldn’t be holding any state as the parent widget might just be adding and removing it from the widget tree — in which case the parent is managing it’s own state of what is being shown and what is not.

- You may create an item widget to be used when displaying a list of some content to the user, for example a list of cakes where each cake is represented by this item widget. To this item widget you’ll pass in a Cake reference which will just be used to populate the content of the item widget. This item widget wouldn’t be saving state, again it is just using the data passed in by its parent to configure its display to the user.

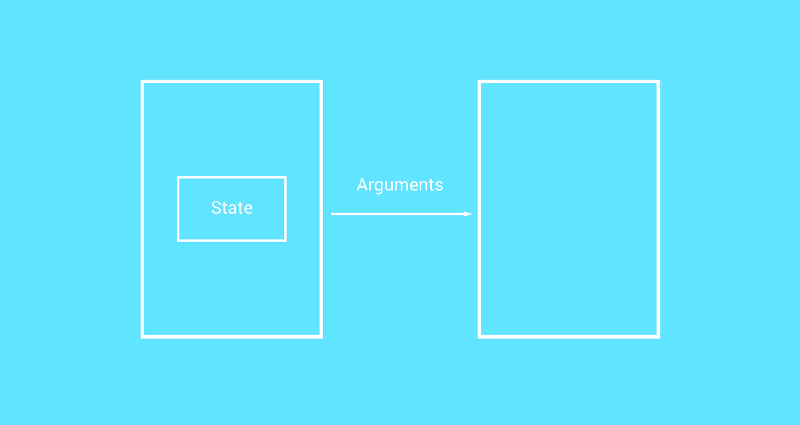

From this we can see that a stateless widget is not dynamic. It doesn’t depend on any data other than that that is passed into it, meaning that the only way it can set how it is represented is when arguments are passed into it’s constructor.

Stateful widgets

Now on the other hand, stateful widgets are dynamic. They allow us to create widgets which can dynamically change their content over time and don’t rely on static states which are passed in during their instantiation. This may change due to user input, some form of asynchronous response or reactively from another form of state change.

For example, we can look at several widgets that we know of which are stateful widgets:

All three of these widgets here are just a few of the stateful widgets from the flutter widget catalog. But what exactly makes these stateful? To begin with, it really helps to dive into the source of these widgets (I won’t do this in this post but you can view the source here). If we open up the source for say, the Image widget, we’ll notice that there is a slightly different look to the file. To begin with, our Image class extends from the StatefulWidget class. Now, just like the previous stateless widgets we look at, our Image constructor still takes in parameters for properties which are to be used by this class. However, the difference is here.

_ImageState createState() => new _ImageState();

This overriden function is used to create the state for our widget. Without going too into specifics about how the Image class works, you’ll notice that the _ImageState of this file is keep a reference to three different properties:

ImageStream _imageStream; ImageInfo _imageInfo; bool _isListeningToStream = false;

The ImageInfo property here is used to load the actual image for the widget. Now, there is a function here called _handleImageChanged which uses the setState function of the State class to essentially say “Hey, something has changed — we need to update our state!”.

setState(() {

_imageInfo = imageInfo;

});

When this happens, the widget is rebuilt with this new state in mind, meaning that the image for the updated imageInfo can be loaded. Here, the Image widget is behaving in a dynamic manner — it’s listening for a change of image reference and then updating it’s state once something changes, therefore it is managing it’s own state and not relying on a parent widget to do so. It’s worth diving into other Stateful widgets to see how they behave, this will also help you to understand better about when something should be either stateful for stateless. For some simple examples of when widgets may hold state:

- Maybe we will create a widget that represents whether or not an item has been bookmarked by our user. Here, our clickable view might hold a reference to isBookmarked — this state would then be set whenever the view is clicked, and the build function of our class would set the Icon based on the value of this isBookmarked field.

- Maybe we will have a widget that will keep a reference to the quantity of the current item being selected, where a ‘+’ icon would increment this value. Here our item widget would keep a quantity state, and every time the ‘+’ icon is pressed the state would be set for this value and the representation of this quantity would be updated within our build function.

I hope this post has helped to make the difference between Stateless and Stateful widgets clear. When using both properly, you can really simplify the structure of your application and make them easier to extend on and debug. Questions or comments? I’d love to hear from you below!